The New Digital Divide

Technology has been an undeniable force in modern society, revolutionising how we work, shop, communicate and entertain. However, many groups lack access to the tools and resources needed to take advantage of digital technology. We are all probably familiar with the digital divide. This is the notion of a gap between those digitally included and those digitally excluded from the benefits of the digital revolution.

In recent years, we have seen the emergence of a new equally pernicious digital divide; how certain socioeconomic groups are more vulnerable to processing by AI algorithms. This is how author Virginia Eubanks describes the poor as profiled, policed and punished by high-tech tools. (Eubanks). Or as Cathy O'Neill highlighted in her seminal book Weapons of Math Destruction, "the privileged, we'll see time and again, are processed by people, the masses by machines" (O'Neil).

In this article, I will examine the traditional notion of the digital divide and this new emerging issue of an algorithm and AI digital divide. For each, I will look at causes, implications and potential solutions.

The Existing Digital Divide

According to an article in the Harvard Business Review (Chakravorti), there are four components of the causes of the digital divide that we need to consider: infrastructure, inclusivity, institutions and digital proficiency. For infrastructure, we need to consider whether the internet or broadband is available in a particular area. This is a problem in developing countries, and even more so in rural areas of developing countries.

McKinsey estimated that in the US alone, 24 million people lack access to high-speed internet, and many more cannot connect due to gaps in digital equity and literacy (McKinsey). Many other root causes contribute to the digital divide, including educational, language, age and skills barriers.

Closing the digital divide is essential for numerous reasons, including promoting social inclusion, expanding economic opportunities, and increasing civic engagement among all members of society. People who are digitally excluded are less likely to be able to find work, as many professions are increasingly reliant on digital skills. Internet access is also increasingly crucial for civic engagement, with many organisations making it easier to take political action online.

The implications of the digital divide were evident during the pandemic with the move to working from home and online learning. During the pandemic, up to 20% of US teenagers reported having unreliable internet access, which restricted them from completing homework (Chakravorti).

The OECD has stated that 'children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantage grow up to earn as much as 20% less as adults than those with more favourable childhoods' (OECD). While the digital divide is only one factor contributing to socioeconomic disadvantage, it is undoubtedly one factor we can start to address.

Solutions to removing or reducing the digital divide come from the public and private sectors. The US government has allocated over 100 billion USD to assist states in bringing high-speed internet access to every US household. Google offered free wi-fi in public places for several years in certain countries, including India, Mexico, Thailand and South Africa. But addressing the digital divide is not just the morally right thing to do. There are economic benefits too. A study by Deloitte estimated that the US could have created an additional 875000 jobs and 186 billion USD more in economic output in 2019 if it had increased broadband access by 10% in 2014 (Chakravorti).

The New Digital Divide

The abundance of big data, developments in computer technology, and algorithms have led to giant leaps in AI technology adoption in recent years. Machine learning is a component of artificial intelligence. We experience it every day: a recommendation of a new TV show to binge-watch on Netflix, email spam being detected and redirected to your spam folder or your bank using machine learning to help avoid fraud on your credit card.

However, we have recently seen more pernicious and dangerous uses of machine learning. These include what I consider a new digital divide, the growing trend where those from lower socioeconomic groups are subject to processing and targeting disproportionately by AI algorithms and systems. I am a firm believer that AI is and can be a force for good. And it has the potential to help us solve the existential crises that we face as a species – climate change, biodiversity and food security. But we must be mindful of AI's potential negative sides, including this new digital divide.

Cathy O'Neill's book Weapons of Math Destruction discusses the impact of these pervasive algorithms, e.g., those used for recruitment or loan applications. For example, consider the difference in how you would be treated if you applied for an entry-level job at Walmart in the US instead of a senior executive position on Wall Street. In the first example, you will be invariably screened by an AI algorithm. In contrast, in the second example, you will probably get the personal and human touch and deal in person with an executive recruiter.

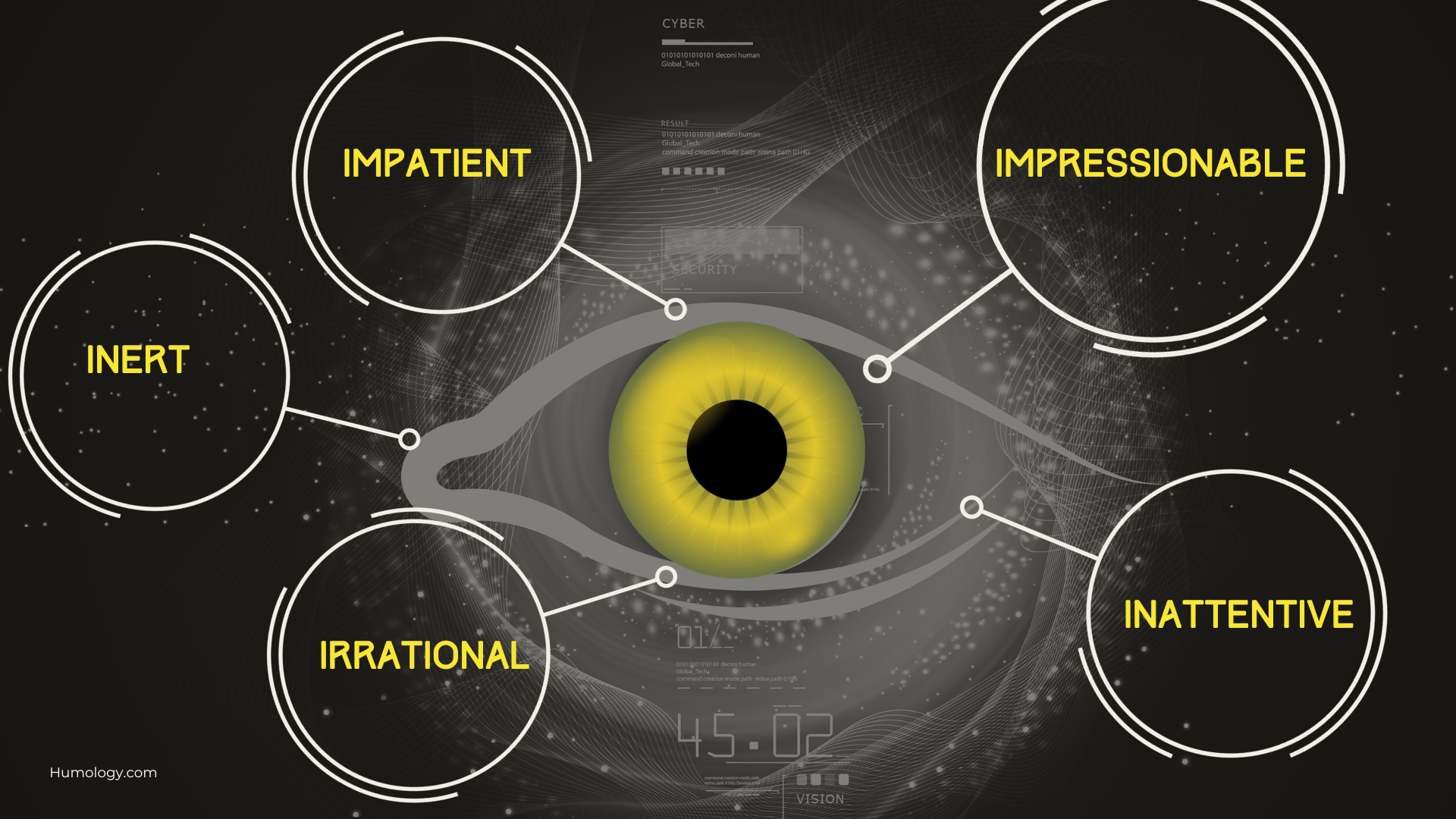

O'Neill outlines three properties of a WMD (Weapon of Math Destruction): opacity, scale and damage. For opacity, we need to consider that even if the person knows they are being modelled, do they know how the model works or is going to be applied? Sometimes companies claim it is their secret sauce or IP or claim the black box effect. For scale, consider whether the WMD impacts one use case or population or can scale exponentially and impact society. Under damage, we can compare the impact of an algorithm that suggests an item to buy (Amazon) or a program to watch (Netflix) with an algorithm that determines whether you get a job, qualify for a loan or even the length of prison sentence you get.

O'Neill urges us, as a society, to use the power and potential of machine learning algorithms to reach out to underprivileged groups with the resources they need instead of punishing them when they face crime, poverty or education challenges. On a practical level, O'Neill advocates a Hippocratic Oath for data scientists and those involved with AI algorithms. She cites the example of the oath created by two financial engineers following the 2008 financial crash. The oath includes several statements, including 'I understand that my work may have enormous effects on society and the economy, many of them beyond my comprehension' (O'Neil).

Equally as passionate about this topic is the author, Virginia Eubanks. To research her book Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor (Eubanks) she spent several years researching examples in the US where poor or disadvantaged communities have suffered from high tech tools and systems, including AI algorithms. In one example, she examined how the US state of Indiana awarded a 1.2 billion USD contract to privatise and automate welfare eligibility, resulting in thousands losing benefits and the state eventually suing IBM and ACS, who had been awarded the contract.

Eubank coined the phrase the digital poorhouse to describe how these high-tech tools are used disproportionately to profile, police and punish lower socioeconomic groups. She traces this approach and mindset back to the days of the original county poorhouses in the US in the 19th century, through the scientific charity movement, which commenced in the early 20th century, right through to the modern day, where algorithms and AI are utilised. She implores those who build these systems, e.g., data scientists and machine learning engineers, to consider the unintended consequences of these tools by asking two questions. "Does the tool increase the self-determination and agency of the poor' and 'would the tool be tolerated if it was targeted at non-poor people?" (Eubanks).

Like O'Neill, Eubank also advocates for a Hippocratic oath for those involved in AI. I particularly liked the final principle she proposes as part of this oath. "I will remember that the technologies I design are not aimed at data points, probabilities or patterns, but at human beings" (Eubanks).

I think this is excellent advice for everyone involved with these technologies. That includes tech start-up founders, AI specialists, data scientists and those implementing these technologies into organisations, including project managers and change managers.

I advocate for a proactive and ethical approach to developing and deploying these AI systems. Somebody once joked that ethics is like the company dishwasher. Everyone is responsible for emptying it, and we all benefit from it. But the person who cares most about it will end up doing it! This is true of ethics but perhaps even more so for the more specific domain of ethics in artificial intelligence. But we can't afford to leave this issue to someone else to address, and I certainly feel we can't afford to leave the matter to a select Tech Brotopia to sort out. After all, Big Tech is often guilty of using the approach that it is easier to beg for forgiveness than to seek permission. We all have a part to play and need to be vigilant.

We only have to look to China's social credit system for a view of a dystopian future if we are not vigilant about how AI can be used to segment, rank and ultimately discriminate against certain individuals and groups.

As Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, said, "when people's lives, livelihoods, and dignity are on the line, AI must be developed and deployed with care and oversight" (Buolamwini).

References

Buolamwini, Joy. "Artificial Intelligence Has a Problem with Gender and Racial Bias. Here's How to Solve It." Time, Time, 7 Feb. 2019, time.com/5520558/artificial-intelligence-racial-gender-bias/. Accessed 3 July 2019.

Chakravorti, Bhaskar. "How to Close the Digital Divide in the US" Harvard Business Review, 20 July 2021, hbr.org/2021/07/how-to-close-the-digital-divide-in-the-u-s.

Eubanks, Virginia. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin's Press, 2018.

McKinsey. "The Digital Divide: Are US States Closing the Gap? | McKinsey." Www.mckinsey.com, 1 June 2022, www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/are-states-ready-to-close-the-us-digital-divide. Accessed 17 July 2022.

O'Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. London, Penguin Books, 2018.

OECD. "Observatory on Social Mobility and Equal Opportunity - OECD." Www.oecd.org, www.oecd.org/wise/observatory-social-mobility-equal-opportunity/. Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.