The Infinite To-Do List: AI Could End Busywork (But It Probably Won’t)

In 1965, Time magazine declared that by 2000, Americans would work just 20 hours a week, retiring at 50 with ‘a guaranteed income for life.’ “Many scientists hope that in time the computer will allow man to return to the Hellenic concept of leisure, in which the Greeks had time to cultivate their minds and improve their environment while slaves did all the labor,” the article continued. The slaves, in modern Hellenism, would be the computers.

Yet here we are, a quarter century after that prediction, grinding through intense work weeks while doomscrolling through other people’s vacations and wellness rituals. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Every time technology offers to save us time, we invent new ways to stay busy. Email was supposed to kill paperwork. Instead, we send 300 billion emails a year. Slack was supposed to kill email. Instead, we send 1.5bn messages per week.

History is littered with predictions about technology freeing us from work:

💡Aristotle (350 BCE): ‘If every tool could perform its own work, slavery would be unnecessary.’

💡John Maynard Keynes (1930): ‘Our grandchildren will work three hours a day.’

💡 Fei-Fei Li, Professor of Computer Science at Stanford University (2020s): ‘I imagine a world in which AI is going to make us work more productively, live longer, and have cleaner energy.’

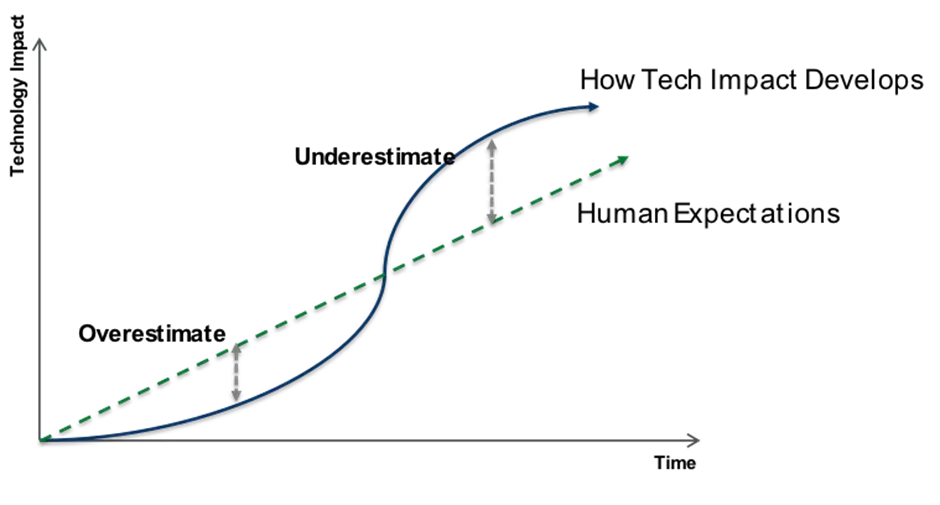

These visionaries agreed on one thing: Technology should serve humans. But history shows we’d rather serve technology. With every technological leap forward we tend to follow Amara’s Law: we overestimate liberation, underestimate adaptation. We don’t eliminate work; we upgrade it.

Amara’s Law states that we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run

Productivity inflation isn’t a glitch — it’s deeply ingrained in our human nature. History whispers to us ominously: When we gain freedom, we invent new ways to lose it. As long as we equate busyness with self-worth, technology may never release us from the daily grind.

Let’s call this what it is: productivity inflation. Not the gap between wages and output, but the gap between the promise of emerging technologies (give us back our time) and what we actually do with the tools that are available to us (fill that time with more work).

The AI Promise vs. The Reality of Work

Tech leaders are at pains to herald AI as the ultimate moment we’ve been waiting for — an uber tool to supercharge our creativity, eliminate drudgery, and finally give us the space to think. Sam Altman calls AI “the greatest force for economic empowerment in history.” Elon Musk describes it as “the most powerful tool for creativity that has ever been created.”

The vision is as old as time itself: technology takes care of the busywork, and humans get to focus on big-picture thinking, strategy, and innovation. More time for ideas. More time for deep work. More time for… being human.

In some ways, perhaps that’s already happening. AI is handling marketing copy, churning out social media updates, automating reports, streamlining customer service. Soon, writing an email might take seconds, not minutes. Content creation could be as simple as pressing a button. Productivity, in the traditional sense, is skyrocketing.

And what then?

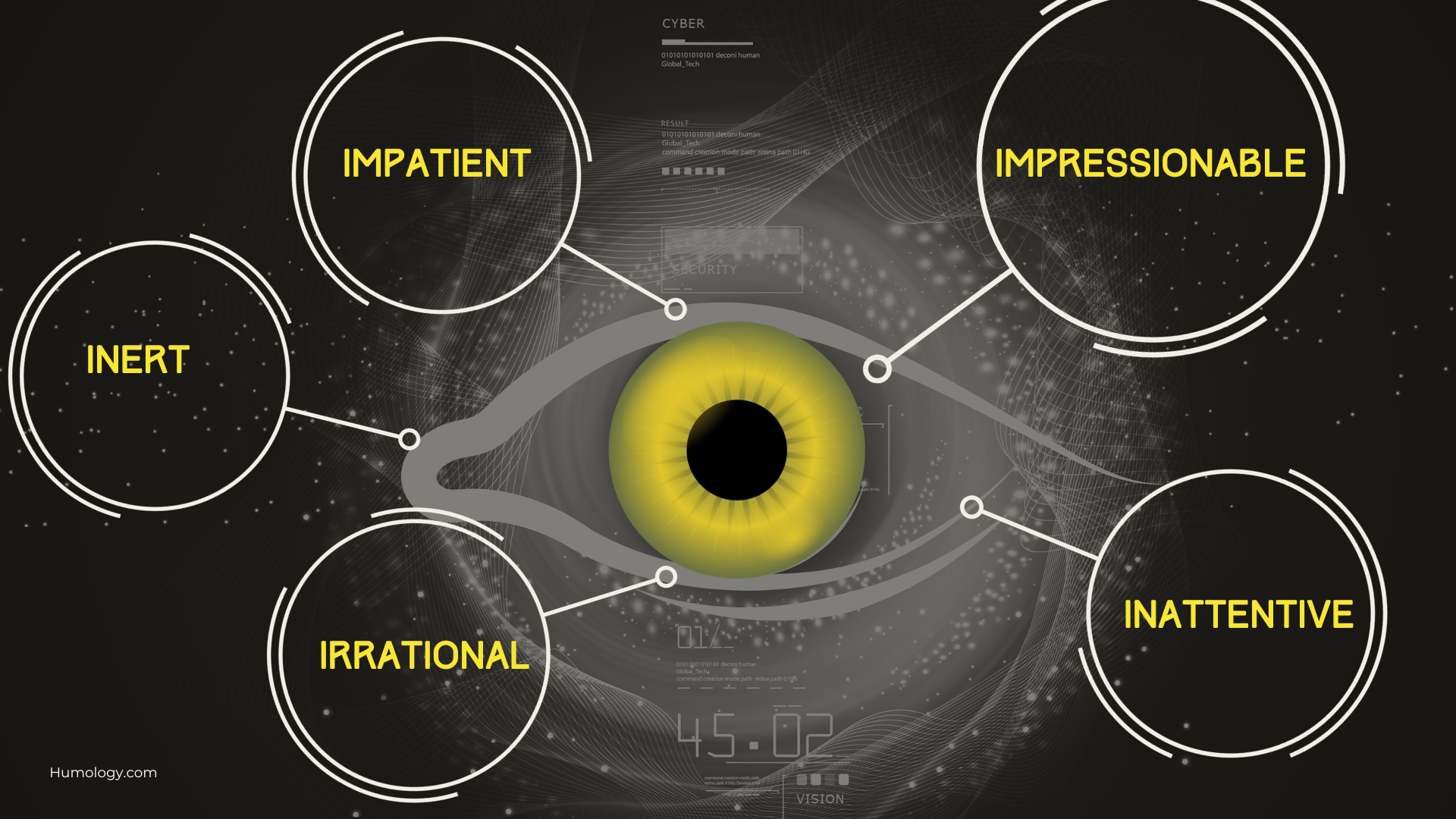

If work becomes frictionless, do we actually work less, or do expectations of work output continue to rise? If writing an email takes seconds, will we send ten times as many? If AI can generate market reports instantly, will decision-makers be expected to act just as fast? If we continue to point a fire-hose of information at the human brain, will we become the ultimate bottleneck, preventing all and any further progress?

And what then?

If history tells us one thing, it’s that every time we make create efficiencies at work, we don’t slow down — we speed up.

Over 2,000 years ago, Aristotle predicted machines could abolish slavery. Instead, we enslaved ourselves to productivity. Why? Because humans don’t know how to stop. This isn’t a new story. Every technological leap — no matter how revolutionary — has promised to free us from labour. And yet, every time, we find ourselves working more, not less. AI has the potential to put our to-do lists on steroids, turning them into infinite scrolls. Do we want that future for ourselves? A confluence of social media trends, information overload, and greater work efficiencies?

If the past can at all inform us of our future, the Industrial Revolution brought machines that could produce goods faster than ever before. But instead of shortening the workday, factories pushed for higher quotas, longer hours, and relentless efficiency.

The introduction of computers was supposed to eliminate paperwork. Instead, it created email, spreadsheets, and an always-on work culture where we’re expected to respond instantly. Smartphones exacerbated the trend giving us the ability to work from anywhere — but now, work follows us everywhere.

The problem isn’t in the code — it’s in our cortex.

Why Do We Keep Falling into This Trap?

‘The faster I go, the behinder I get’

If every technological leap has led to more time to work instead of more time to live, maybe the problem isn’t the technology — it’s us. Why do we default to doing more instead of using technology to slow down?

To be perfectly honest, I’m not sure I fully understand why this feels like an inevitability — but I am observing myself falling into the same pattern over and over again. I’ve quickly become hooked on using AI as a thought partner, as a research partner, and as a productivity booster. What’s really going on when my actions speak louder than my words?

The Brain Layer: Are we hard-wired for busyness?

⏳Instant Gratification Bias

Humans crave quick wins. Checking tasks off feels good. Watching our output pile up makes us feel accomplished. So, we fill the space that AI frees up — not with rest, but with more tasks. It helps us feel a sense of achievement. But wait? That doesn’t explain how much time we spend doomscrolling, right?

❗The “Mere Urgency Effect”:

Studies demonstrate that we are more likely to perform unimportant tasks (i.e., tasks with objectively lower payoffs) over important tasks (i.e., tasks with objectively better payoffs), when the unimportant tasks are characterized merely by spurious urgency (e.g., an illusion of expiration) Link

Could the problem be in the definition of what we call ‘productivity’? Cal Newport, author of Deep Work and Slow Productivity, posits that as more jobs became knowledge-based roles filled by thinkers and planners who produce ideas and strategies rather than physical goods, the metrics for productivity failed to evolve. The absence of clear success indicators for knowledge work led organisations to continue to depend on visible busyness as evidence of productivity. Newport argues that productivity should be redefined from merely completing a high volume of tasks to achieving high-quality, meaningful results. If we took this approach, would we be less likely to use AI to generate more and more content, and use it as a creative partner in producing higher-quality meaningful content?

The Identity Layer: Do we wear busyness as a badge of honour

⚒️ Self-Worth & Work Culture

We’ve been conditioned to see busyness as a measure of success. If AI takes over too much, does our work still have value? Are we still useful? The idea of doing less often feels unnatural, even uncomfortable. Thinking back to the years I spent in senior corporate roles in a large tech company, I would often respond to ‘Hi Joanne, how are you?” with ‘Oh you know… meeting myself coming round corners”. This wans’t a cry for help — it was a flex. The normalisation of being overwhelmed with things to do is not what I want for future-me, and my children.

🧠 The “Productivity Guilt” Paradox:

A 2024 Asana survey found 78% of knowledge workers feel guilty when they’re not busy — even if their work is done! However, busyness and productivity are not the same thing. Busying ourselves with busy work is form of toxic productivity that only leads to burnout. I wore that badge with pride for many years. Since leaving the corporate grind, my relationship with work needs constant fine-tuning like a constant tug-of-war to balance freedom, money, and doing great work.

While productivity guilt can seed itself from our internal dialogue leading to shame and self-criticism when we haven’t met our own expectations or haven’t worked ‘hard’ enough, external guilt also plays a role. Societal norms and virtue signalling of hard work can also feed the greed machine that enslaves us to doing, instead of being. So, it seems, while we can offload some tasks to AI, we can’t yet offload our anxiety about appearing productive!

The System Layer: Capitalism’s Relentless Pursuit of More.

💰 Capitalism & Economic Incentives

More efficiency doesn’t lead to more leisure — it leads to higher profit margins, reduced headcount, and increased output expectations. The efficiency gains don’t belong to workers; they get absorbed into business metrics.

Meta’s ‘year of efficiency’ in 2023 continued into 2025 efforts to ‘cut low performers faster’. The Musk-led DOGE in the US have sent emails to employees asking them to summarise their accomplishments via email. Failure to respond by the short deadline will be taken as a resignation. The message is clear — our obsession with doing more with less is set to continue. There is no room for ‘being’ — (maybe ‘being’ a human is woke? 🤔) Either way, if you’re not as obsessed with ‘doing’ as your employer is, maybe you should work somewhere else.

The Hidden Cost: The ‘Infinite Scroll of Work’

AI is churning out content, emails, reports, marketing copy faster than ever, creating more noise in an already-crowded world and pushing many more micro-decisions our way every day. Instead of freeing up space for deep thinking, AI could end up overwhelming our precious cognitive resources to filter out information overload, disinformation and fake content. What a waste of our incredible human ingenuity that would be!

The increasing expectation of rapid execution might further fuel our innate desire for instancy, making us ever more impatient. Technological determinism — the idea that tools shape society in predictable, unavoidable ways — has long fuelled the belief that progress is automatic. If we build smarter machines, the logic goes, we’ll inevitably work less. But determinism is a lazy cop out relieving us from making important decisions about our future. Tools don’t dictate outcomes. Human behaviour does.

We have an important choice to make — because technology’s potentiality is closely linked with our intentionality.

📌 Option 1: Passive Adoption (The Path of Least Resistance)

- Infinite To-Do Lists: AI becomes a “productivity steroid,” as one engineer told me. “My team uses GPT-4 to draft code — so now we’re expected to ship 10x more features in half the time.”

- Technostress Ubiquity: Burnout becomes the default as we juggle AI’s 24/7 output. Burnout isn’t a bug of productivity business model — it’s a core design feature.

📌 Option 2: Intentional Reinvention (The Path Less Scrolled)

- The 4-day week: Kickstarter uses AI to automate status meetings, not to extract more work, but to protect time for deep creativity. Result? 73% happier teams, zero drop in output.

- The JOMO Movement: Teams now auto-delete “optional” tasks (Slack updates, meeting recaps) using AI. It’s not about doing more — it’s about doing what matters — choosing important over urgent.

Steve Jobs was half-right: “Technology alone isn’t enough.” AI won’t free us until we stop conflating “being productive” with “busyness.”

Marshall McLuhan famously argued, ‘We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.’ But this shaping isn’t passive. Email didn’t force us to send 300 billion messages a year — we chose to prioritise responsiveness over reflection. AI won’t make us inflate productivity, but we might — by clinging to old metrics of success.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Robert Frost — The Road Not Taken

Every major technological shift forces us to decide: Will we shape technology, or will we let it shape us?