The Human Cost of the Digital Revolution

“Every stress leaves an indelible scar, and the organism pays for its survival after a stressful situation by becoming a little older.”

- Hans Selye, MD, PhD, The Father of Stress

This article is the first in a series on unpacking Technostress and its consequences.

‘Chronic stress is the new normal’ screamed a Forbes headline this month. It stopped me dead in my tracks. Has it really gotten this bad? Like smartphones, stress seems to be a ubiquitous companion as we lurch from crisis to crisis, while sprinting to keep up with the pace of change. Stress thrives whenever there is an imbalance between the demands being made of us and the resources we have available to meet those demands. When our resources are overwhelmed for weeks or months on end, we experience chronic stress — resulting in depleted energy, negative emotions and lower productivity. Worryingly, chronic stress is the lastwarning sign before burnout.

While employee burnout is steadily increasing, global productivity has slumped since the internet went mainstream. Organisations are spooked — 90% of employers are committing to greater investments in mental health, stress and resilience training, along with mindfulness and meditation programs.

However, band-aids don’t fix bullet holes: betting the future of work on wellness supports at the individual level, without addressing the source of increasing stress levels, is unlikely to prove effective.

How did we get here?

Relationship Status: It's Complicated

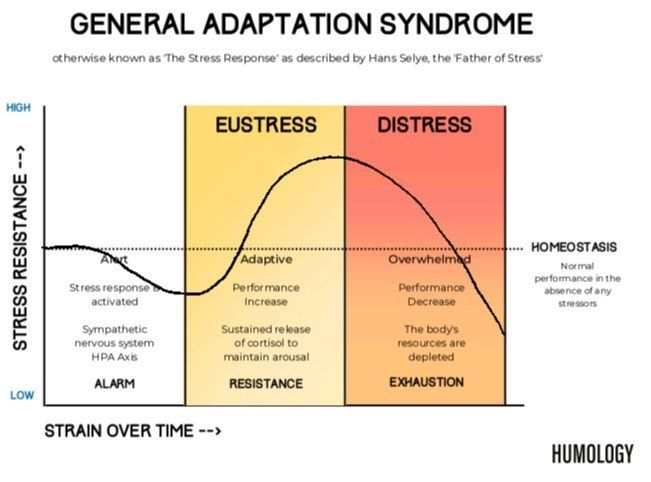

Each of us has a complicated relationship with stress — it can be intoxicating and toxic all at once. A Hungarian endocrinologist called Hans Selye (1907–1982), dubbed the “Father of Stress”, was the first to provide a scientific explanation for biological stress. He described stress that negatively affects us as Distress, while stress that has a positive impact he called Eustress. In small doses, stress helps us stay alert, fuels motivation, and supports us as we adapt to new experiences. However, when the scales is tipped towards distress, we feel overwhelmed, exhausted and depleted.

Selye broke down his model of stress into three distinct stages — originally called GAS (General Adaptation Syndrome), now colloquially known as The Stress Response. As we move through each stage, our resistance to stress changes, as follows:

Stage 1 — Alarm

When a stressor is detected, the body responds with a “fight-or-flight” response. The sympathetic nervous system is stimulated, and the body’s resources are mobilized to meet the perceived threat or danger.

Stage 2 — Resistance

The body focuses resources in dealing with the stressor and remains on high alert until the threat subsides.

Stage 3 — Exhaustion

If the stressor(s) continue to overwhelm the body’s capacity, our resources become exhausted. This stage is the home of chronic stress and, eventually, burnout.

The human stress response involves many physiological components. First, the brain initiates the most immediate response signalling the adrenal glands to release epinephrine and norepinephrine. Then, the hypothalamus and pituitary activate another part of the adrenals to release cortisol. The nervous system responds by initiating behavioral responses like alertness, focus, and reduction of pain receptors. The sympathetic nervous system increases the heart rate and releases fuel to help fight or flee from danger. It redirects blood flow to the heart, muscles and brain, away from digestive processes. To accommodate these demands there is a vast increase in energy production and utilisation of nutrients and fluids in the body. Once the stressful situation has passed, the brain signals these responses to be “turned off” and finally recovery and relaxation allow the body to re-establish balance (homeostasis) in all systems.

However, what happens when these perceived threats don’t dissipate? What is the consequence of facing a relentless bombardment of fear and uncertainty?

When our bodies are repeatedly flooded with stress hormones, our resources are depleted, compromising our ability to respond quickly to threats even when we need them most. A key element of the stress response that is missing in modern culture is recovery. While you might allow some recovery time after being chased by a lion, we don’t often afford ourselves the opportunity to recover following a stressful day at work, or a stressful commute on our way home. Chronic stress is insidious and can sneak up on us when we’re busy keeping all the balls in the air for an extended amount of time: the price we pay is significant. Prolonged cortisol levels can lead to a loss of long-term memory and harm our attention and executive functioning. We become anxious and our cognitive flexibility is stunted. We start to shut out new ideas in a misguided attempt to protect ourselves from any and all potential threats. Put simply, we are in a continuous state of self-defence.

A New Stressor for the Digital Age

The human brain has evolved over millions of years to efficiently process threats (like lions or angry bears) and rewards (like food or sex) as a matter of survival. In modern times, technology has introduced a new kind of threat — information overload — and an entirely new reward system — likes and followers. Both can be addictive and potentially damaging to our brains. In an ideal world, our everyday use of technology would enhance eustress and mitigate distress. However, mounting evidence shows that technology-induced stress is reaching pandemic proportions and has the potential to undermine organisational agility and the adoption of emerging technologies.

Technostress is the new uber-stressor of our time. Spurred on by the pervasive use of technology in our lives and the increased digitalisation of work, this new source of stress transcends geographical and cultural barriers, and is wreaking havoc in organisations and societies. A constant barrage of new devices and apps is creating unprecedented demands on our palaeolithic brains, while our dopamine receptors are being rewired by the digital age leaving many of us feeling frazzled and unfulfilled by the mundanity of work.

The term technostress was first introduced by the American psychotherapist Craig Brod in 1984. Even before the digital age, Brod described this new form of stress as “a modern disease of adaptation caused by an inability to cope with the new computer technologies in a healthy manner.” While it is no longer considered a disease, technostress acts as a key multiplier of work-related stress, actively compounding the intensity of existing stressors in life and in the workplace.

As with everyday stress, technostress can have both positive and negative impacts. When technology induces eustress, we are challenged and motivated by the opportunity to grow and learn. In the eustress zone, tech apps can deliver satisfaction and joy, help us make decisions and enable us to adapt with ease. With technology at its best, organisations can improve performance, efficiency, and innovation. On the downside, techno-distress can make employees feel undervalued and under recognised.

Technostress is typically triggered in the following circumstances:

- When there is a high dependency on technology

- When we perceive a gap between what we know and what we need to know, and

- We detect a change in work culture brought about by technology

This type of stress gives way to physiological symptoms like fatigue, irritability, and insomnia, and a host of psychological symptoms such as frustration, additional mental load, scepticism, a reduction in job satisfaction, reduced commitment, and lower productivity.

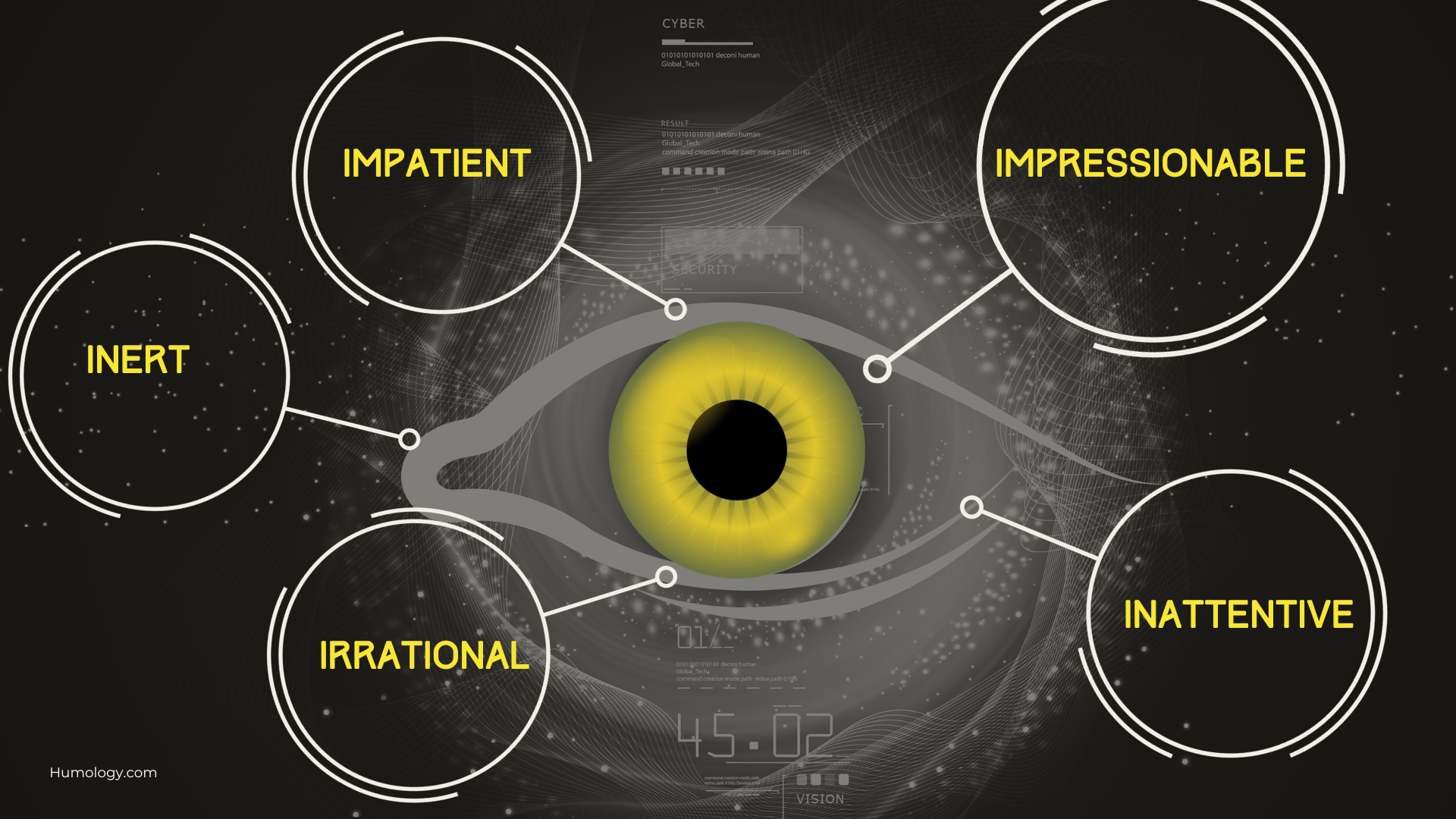

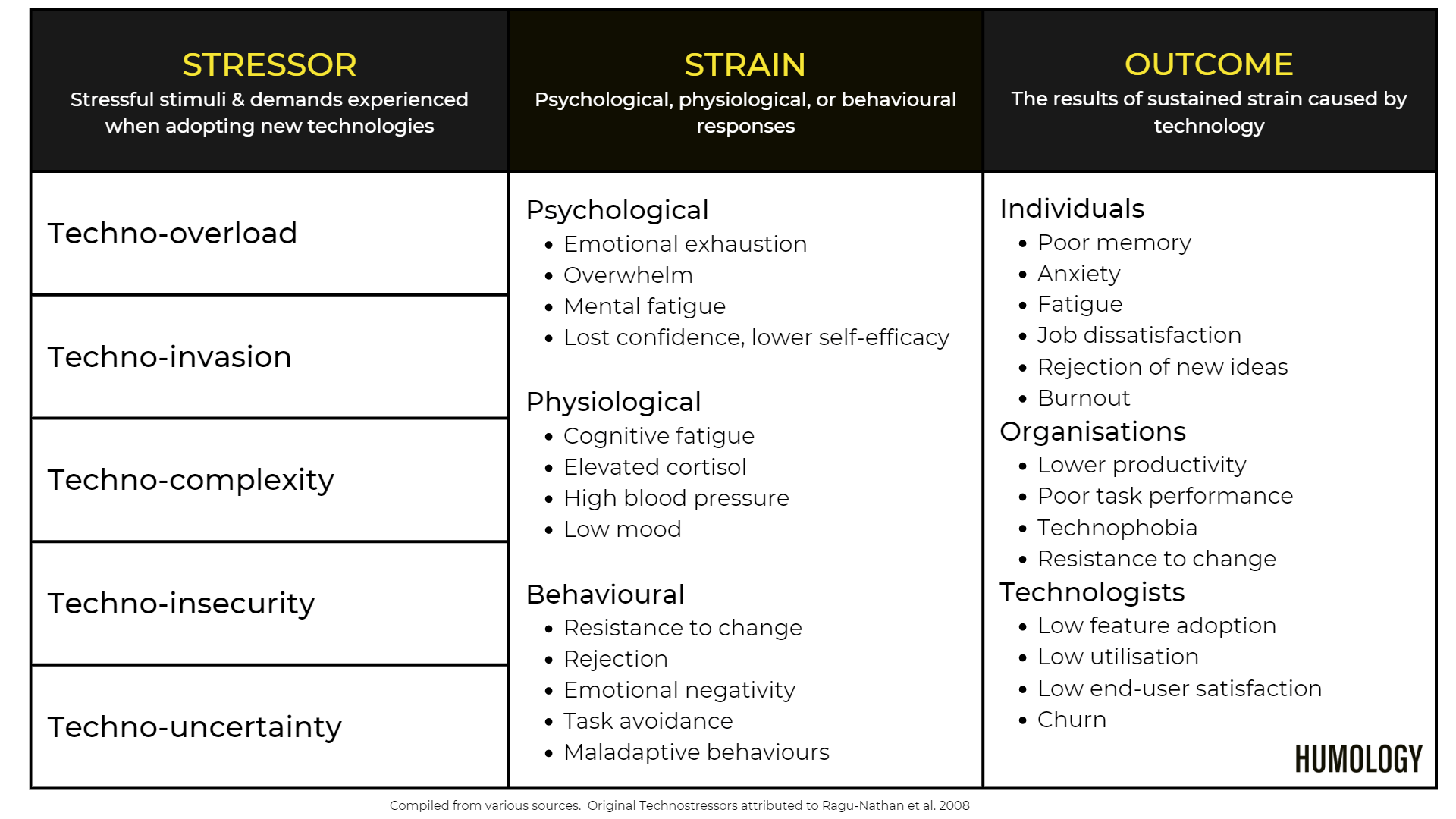

Unpacking Technostress

Research into technostress is picking up in recent years as we try to understand the underlying causes of low adoption, failed digital transformations, and falling productivity at work. While new findings continue to emerge, technostress is most frequently analysed across five key domains. Each domain acts as an individual ‘stressor’ contributing to total levels of technostress. These stressors act as hidden threats to digital adoption and have the potential to derail even the most carefully considered tech implementations.

The five key domains are:

- Techno-overload

- Techno-invasion

- Techno-complexity

- Techno-insecurity

- Techno-uncertainty

Techno-overload

Too much to pay attention to, not enough mental space. We’ve learned that our human capacity to adapt to technological changes is compromised by infobesity and choice overload in recent years. Every day a multitude of applications churns out mammoth quantities of information and our brains feel compelled to ingest, digest and respond to it all. The additional information, coupled with an array of new formats, all add to the mental gymnastics our brains need to perform to keep up.

Trying to keep pace with the latest updates and features across all our applications is next to impossible. New features often signal something new for us to learn and adapt to. When we don’t have the time or the mental capacity to engage with every update vying for our attention, we either procrastinate, or blindly accept the updates and pray we haven’t broken anything. Rarely do we mindfully adopt new features or product updates in the way that product managers hope we might. Every time we take a shortcut in the interest of efficiency we add weight to imposter syndrome and develop an unspoken fear of being exposed for being asleep at the wheel.

Doing things differently can also inadvertently add more workload for an unsuspecting human-in-the-loop. While technology processes tasks faster, it may inadvertently create more work when the output passes to a human. The pressure to adapt and maintain productivity at the same time is a common source of anxiety in the digital age of work!

Techno-invasion

Accelerated by the pandemic, work apps have invaded our personal devices, our personal space, and our personal lives. The lines of demarcation between work and home have been irretrievably blurred, making it harder to disengage from work or focus on replenishment. Our ‘always on’ culture means that we’re more available, to more people, more of the time: while we may be out of sight when working remotely, we are rarely out of contact.

In an effort to get a handle on productivity, an increasing number of employers have implemented spyware. Ominously dubbed ‘bossware’ or ‘tattleware’, employee-monitoring software like Prodoscore use machine learning, AI and NLP across thousands of data points to provide ‘productivity intelligence’ to employers. At the receiving end, persistent surveillance can be unnerving and erode trust. When trust is eroded, anxiety levels are elevated, and poorer performance ensues.

Techno-complexity

Every one of us has encountered a new piece of technology that comes with more features and functions than we could possibly ever need or use. The sheer variety of functions and seemingly endless possibilities can intimidate any user. Surveys show that employees use only 40% of the features of any software application, and 61% of organisations admit to being surprised by the complexity of the ‘easy to use’ software they’ve purchased. It’s no wonder we’re disillusioned with digital transformations that promised to make our lives easier!

While training can help — a one-size-fits-all approach to classroom training is rarely an effective way to drive digital adoption. We don’t have the time and mental resources to invest in learning and understanding how to use each feature, so we do our best to intuitively navigate new systems, often feeling helpless and inadequate as we do so.

Techno-insecurity

As technology expands its corporate footprint, many employees are naturally anxious to understand how they will be impacted. The longer-term effects are not always obvious or even thought through in advance. Will my current skills become obsolete? What is I can’t keep up with the changes? How will my performance be measured in the Digital Age? Feelings of inadequacy, coupled with uncertainty, can negatively impact our relationship with technology, even leading to technophobia.

Techno-uncertainty

We accept that technology is advancing at an increasing rate and we’re under pressure to learn and adapt to new tools and features at a faster pace than ever before. The knowledge and skills we have spent years perfecting are becoming outdated at an accelerated pace and the demands on relearning can exhaust our mental capacities.

Ultimately, when the effort we need to expend to achieve an outcome appears to outweigh the value derived from using the tool, our self-competence is eroded and frustration starts to build. The end result is disengagement at best, or computer rage at worst

[They say a sense of humour may be God's antidote to frustration - take a minute to watch these poor tortured souls rage against the machine 😊]

Joking aside, the rise of digitalisation at work is having a silent, yet significant, impact on individuals, organisations, and technology professionals. The Stressor-Strain-Outcome framework is a useful tool to demonstrate the connection between different stressors and the results they create in the world. Even a cursory analysis reveals a variety of new psychological, physiological and behavioural problems caused by the digitalisation of work. These stresses have real-world consequences.

Too often, we’re captivated by the latest and greatest technologies without considering the toll that they’re taking on our ability to adapt. It’s time to prioritise human evolution above technological revolution.

This blog is the first in a series focussed on Technostress and its impacts for individuals, organisations and technologists. Over the next few months, I will be diving into these impacts and covering strategies aimed at reducing techno-distress. Subscribe below to receive future blogs in this series.