What Can Change Management Learn from Behavioural Economics?

Change management is a discipline that has borrowed quite successfully and rightly from other disciplines, including psychology, coaching, management consulting, project management, counselling and data analytics. I believe change management can also learn a lot from behavioural economics. If change management and behavioural economics were to meet at a party, they'd have a lot to discuss!

I want to share my thoughts on how you can use fundamental theories and wisdom from behavioural economics to sharply increase your success rate when making significant changes in your organisation. As part of our research for our book, my co-author and I completed a course in Behavioural Economics from Rottman University in Canada. The course provided me with fascinating insights into the behavioural economics theories that explain the difference between what people should do and what they end up doing when making economic decisions. I was struck by how many of these insights we could apply to change management.

Behavioural economics combines economic and psychological principles for understanding how people behave. It differs from neoclassical economics, which assumes that most people have well-defined preferences and make selfless decisions based on those preferences.

Humans are complex and multifaceted, and the field of behavioural economics is devoted to revealing our vulnerabilities and strengths. Behavioural economists ask us to think laterally about how we could influence behaviour through the right combination of incentives, processes and strategies. By understanding our cognitive biases and other psychological quirks, we can improve our decision-making and benefit from more effective and efficient use of our time and resources.

Before we get into the details, I think it is helpful to explain the distinction between behavioural economics and behavioural science, as these two terms are often conflated or misunderstood. We can consider behavioural science an umbrella term covering all biological and social studies of human behaviour. This discipline includes psychology, sociology and cultural anthropology. Behavioural economics is commonly seen as a sub-science under behavioural science because it uses methodologies typically derived and influenced by behavioural science studies like social psychology.

Richard Thaler is considered by many to be the grandfather of behavioural economics. He received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2017.In Nudge, the bestselling book he wrote with Cass Sunstein, the authors introduced us to econs, choice architecture and nudge theory.

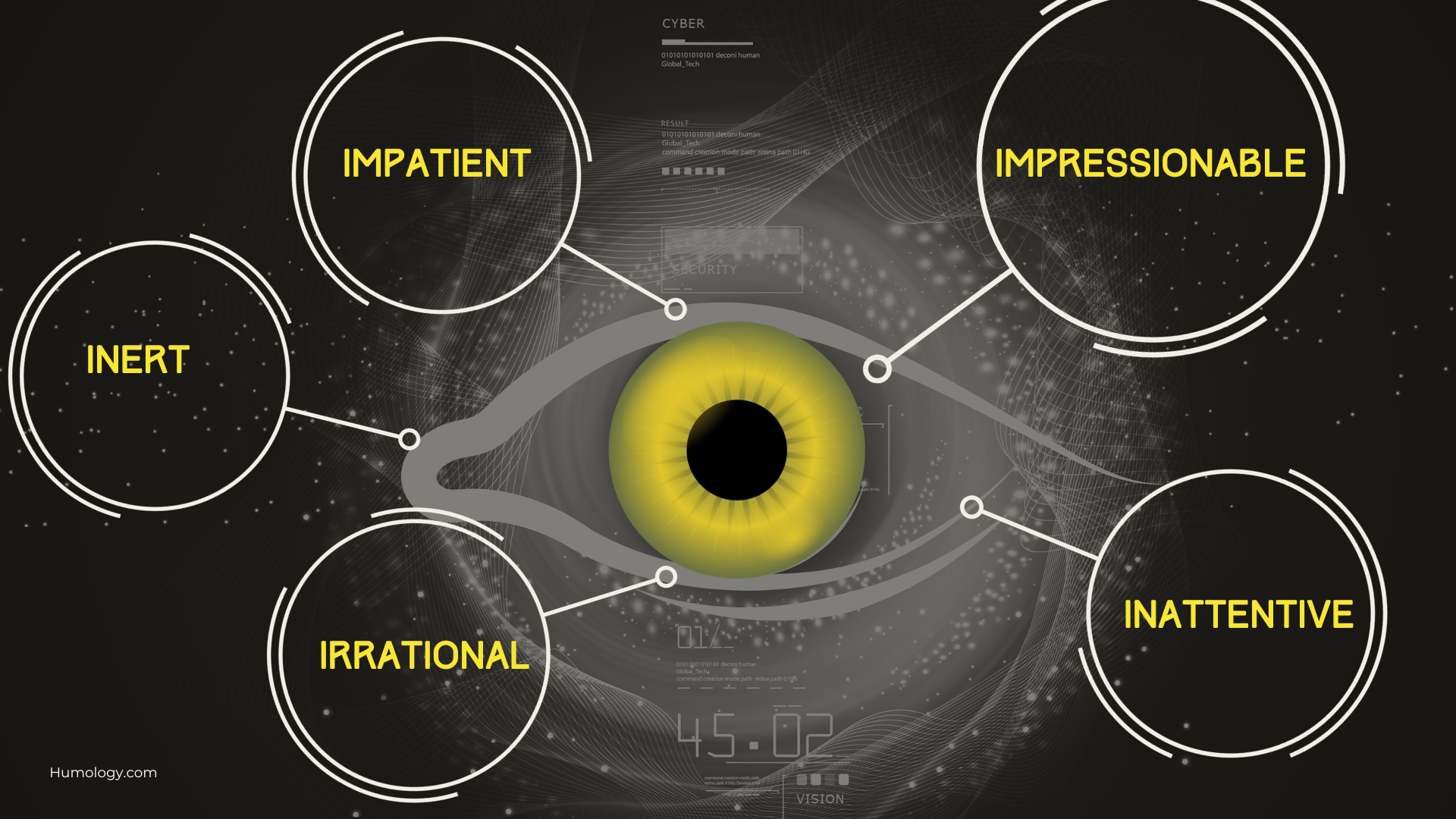

Central to behavioural economics, and what sets it apart from traditional economics, is the concept of econs. Thaler's criticism of conventional economics is that it sometimes assumes that humans are entirely rational creatures, or econs, who always make logical choices in their best interest. By contrast, when making decisions, ordinary people are influenced by many factors when they make economic choices, including biases and defaulting to heuristics or shortcuts.

How often do we assume that stakeholders will always react rationally in change management? Individuals don't decide in a vacuum; their response to change is determined by the nature and consequences of the change, the organisation's history with changes, the type of individual, and their experience of previous changes. Perhaps when we encounter what we perceive to be resistance to change, we should consider if the person's response is entirely rational for them, given their context.

What is Choice Architecture?

Choice architecture Is 'organising the context in which people make decisions'1. We can see examples of choice architects in our everyday lives. A doctor outlining possible treatments to a patient, a personal trainer describing different exercise options to a client, and an HR professional designing a form to enrol new hires into the company pension scheme are all examples of choice architects.

Similarly, change managers often fulfil the role of the choice architect. When we discuss or present our change initiative, we provide a choice to our stakeholders, whether we realise it or not, to either engage or disengage with the change. We present options to stakeholders, so we need to organise the context in which stakeholders make decisions. Thaler has listed six principles of good choice architecture:

- Incentives

- Understanding mapping

- Defaults

- Give feedback

- Expect error

- Structure complex choices

Intro to Thalers Nudge Theory

Nudge theory is based on a book of the same name, written by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler. It focuses on how positive reinforcement and social norms can be used to influence people's behaviour. For example, rewarding someone for something they do can encourage them to repeat the same behaviour in the future. Behavioural economics uses choice architecture to nudge people towards desired behaviour without the use of law or monetary incentives. The fundamental principle is that design decisions can influence decisions even in the absence of heavy-handed regulation. Nudges are subtle ways of getting people to take action. We can consider them "softbargains" because they're not edicts or demands. A significant reason nudging is so compelling is that it encourages people to think for themselves. You're giving them the tools to critically examine the choices presented to them and make the best decisions possible.

Social Nudges

Thaler has highlighted three social nudges that we can also utilise in our change management activities. These are peer pressure, information and priming.

Humans are social creatures, and those around us influence us. We can leverage this by informing our stakeholders about what their peers are doing ,e.g., how many people in the organisation are using the new procedure or have logged into the new IT system. I like to present these details visually in an interactive dashboard on the change initiatives I lead. Change champion networks can also lead the way when leveraging peer pressure. Introducing a social element to your change via Slack or MS teams channels can also help.

Invest the time to ensure that your stakeholders have access to all the information they need and that it is easily accessible. While the change may be the key focus for the change or project team, it will probably be just one of several priorities for most of your stakeholders.

Priming occurs when an 'individual's exposure to a particular stimulus subconsciously influences their response to a subsequent stimulus'. Studies have shown that we are greatly influenced by what we hear, see and read. Change professionals and leaders must be mindful of our language when discussing a change initiative. We should craft key messages carefully, acknowledging that we need to be upfront and honest. When we veer into spin it is easy to lose the trust of our stakeholders.

As humans, we have limited cognitive resources. Every day, we make thousands of different decisions, and our brains conserve energy by using shortcuts to respond quickly. This means that the world is perceived through pre-set lenses rather than a clear one in some cases.

The term "cognitive bias" refers to systematic errors in thinking people make when processing and interpreting information around them, which affects their decisions. A heuristic can be defined as a shortcut or rule of thumb that simplifies decisions. They are used in scenarios where there's an uncertainty, and they involve substituting difficult questions with easier ones.

The Cognitive Bias Coda, available online, lists almost 200 biases affecting our actions and thoughts. While I am not suggesting we need to consider all of these, it can serve as a valuable checklist for significant biases we may want to consider when designing our change interventions.

In their 1974 paper 'Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases', Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman highlighted three critical heuristics; anchoring, availability and representativeness.

Anchoring is the human tendency to first rely on and assimilate new information with whatever they have been exposed to, often setting the tone for all subsequent decision-making. I leverage the anchoring bias on my change initiatives by utilising Simon Sinek's Golden Circle model. When presenting a change or developing key messages, I start with the 'why' of the project before explaining the 'how' and the 'what'. This ensures that stakeholders are anchored to the why before hearing about the how and the what

The availability heuristic is a cognitive bias in which you form opinions based on recent or readily available examples, even if they are not representative of the topic. Suppose you read several reports in a newspaper about burglaries. In that case, you might assume that burglaries are far more common than is the case in your locality. Similarly, a stakeholder might hear a few negative comments about your change initiative and conclude that there is a widespread negative view of the change within the organisation.

The representativeness heuristic is a mental shortcut that we use when estimating probabilities. We often assess how likely something is by determining how similar it is to a prototype that already exists in our minds. For example, a stakeholder might evaluate your project based on their experience of the most recent change they have gone through.

Kahneman has pointed out three biases that are also useful for a change management professional to consider; optimism/overconfidence, loss aversion and the status quo bias.

As change management professionals, how often do we underestimate the duration or complexity of a task? Or perhaps we have worked alongside project management peers who can sometimes underestimate the costs and duration of projects. In addition, I think we all are aware of or have seen first-hand circumstances where a change sponsor has overestimated how enthusiastic stakeholders will be to a particular change initiative.

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that makes individuals feel the pain of loss twice as intensely as they do the pleasure of gain. As a result, people often try to avoid losses in any way they can.

As change management professionals, we need to acknowledge the losses people may feel about a change initiative and articulate and emphasise the positive or gains. One way of doing this is to effectively communicate the WIIFM (What's in It for Me) to all of our stakeholder groups.

The status quo basis is arguably the most critical bias that change management professionals need to be aware of and address. This bias explains our strong preference for the current state and can manifest as resistance to change. Occasionally, I needed to nudge my impacted stakeholders out of their status quo bias on some of the change initiatives I led. Sometimes I have been fortunate enough to have a burning platform to point to, and other times, I have used a combination of various change interventions and coaching to move people out of this bias. This bias also underlines the importance of sustaining or reinforcing activities to prevent impacted stakeholders from slipping back into old processes or systems after the focus and excitement of the change have elapsed.

If we choose to apply choice architecture or nudges on our change initiatives, we need to pay extra attention to being empathetic and respectful of our impacted stakeholders. Without this we are in danger of straying into manipulation.

Practical Steps

So, what are the practical steps change managers can take to start to leverage the principles discussed in this article? I recommend you start by taking a deep dive into the works of Thaler, Kahneman and others, as I have only scratched the surface in this article. Then download the Cognitive Bias Coda and determine which of these resonate with your current change initiative challenges. After that, you are ready to start designing nudges for your change initiative. The Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto have produced an excellent practitioner's guide to nudging. The guide takes you through a detailed process for developing nudges that include four steps; map the context, select the nudge, identify the levers for nudging, and experiment and iterate. I particularly appreciated their process for identifying bottlenecks for your nudges.

Change management is an ever-evolving discipline which is one of the reasons that I find working in it so exciting and rewarding. I hope you will find that you can add the concepts discussed in this article to your change management toolkit.

References

Thaler, R. H. and Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. Caravan Books.